Let’s clarify a couple of big truths that help us get the “lay of the land” about the Catholic approach to temptations to sin.

First, temptation itself is not a sin! We are human beings—a complicated and mysterious collection of impulses, thoughts, feelings and desires, over which, sometimes, we have little control. And temptations do not only arise from our own weaknesses and vulnerabilities—they can also originate from the Evil One seeking to distract, delay or derail us. Even Jesus, Himself, was tempted in every way we are, though He did not sin. So experiencing temptation does not mean that one is a hopeless sinner bound for hell.

Second, temptation is not harmless and must be resisted! Just because temptation isn’t itself sinful, that doesn’t give us leave to seek, welcome or court temptation—as we allow temptations to gain a foothold in our hearts and minds, temptation moves to choice, thought leads to desire which leads to the engaging of the will. Allowing temptations free rein in our thoughts and hearts is an unwise strategy. It’s playing with fire.

Third, we experience temptation in the depths of our hearts, in our thoughts, in our own desires—but we are not fighting this battle alone! God is not somewhere far off, aloof, waiting to see if we’ll fail. He is beside us, within us, loving us with a power, an eagerness and a vision that we cannot begin to comprehend. God intends good for us—the greatest good. He is not the source of our temptations. The Bible is clear about that—God does not sin and He tempts no one to sin. But He allows us to struggle with temptation for His good purposes—for our greatest good. No matter what temptations we struggle with—God is with us and giving us every help we need to overcome the temptation. We may, through God’s divine Providence, end up with greater virtue, greater graces, than if we hadn’t faced that temptation in the first place. In fact, I think God often allows us to struggle against the most shameful temptations to destroy our pride and grow in humility.

These are the three basic realities Catholics start with: ONE, temptations aren’t in themselves sinful (so don’t despise yourself); TWO, temptations are dangerous to ignore (so don’t excuse yourself); and THREE, God is with you: He is not the source of temptation and He is eager to help you in your struggles (so don’t lose hope).

“Temptation to a certain sin, to any sin whatsoever, might last throughout our whole life, yet it can never make us displeasing to God’s majesty provided we do not take pleasure in it and give consent to it.”

St. Francis de Sales

Now that we have those ideas firmly in mind, let’s talk about how to face and overcome the temptations that come our way. I’ll share two stories to help you remember these tips and techniques.

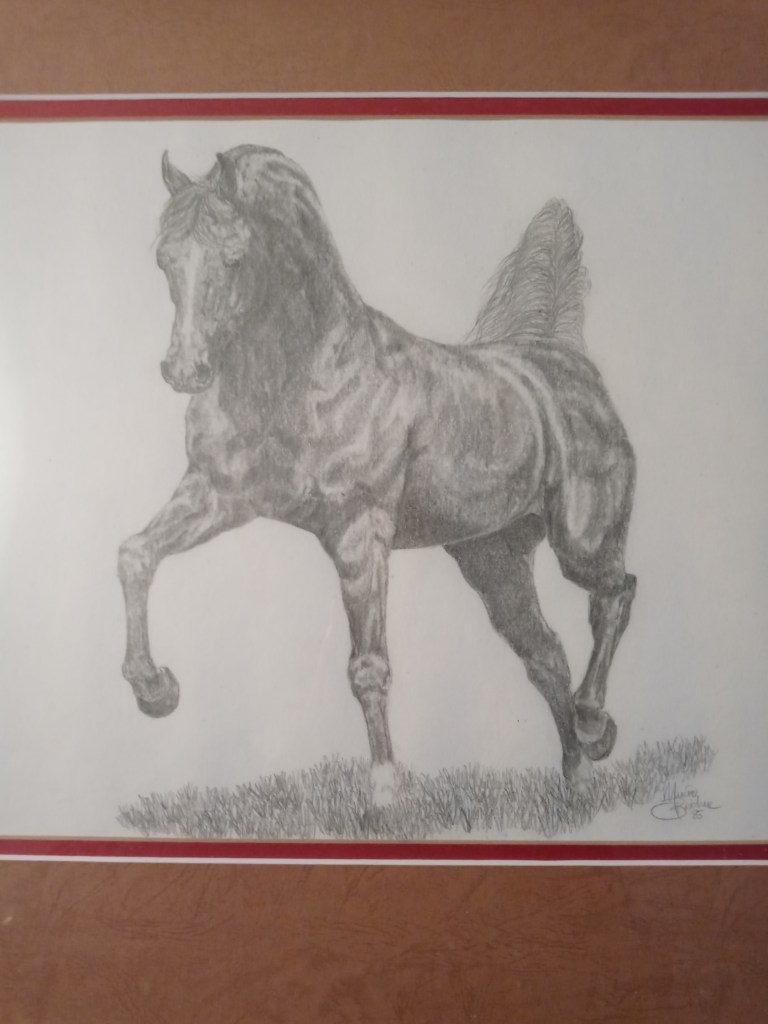

The first story comes out of my passionate love for Arabian horses. Growing up a middle-class kid in the suburbs, I never had a chance to own the horse of my dreams—or any horse! But that didn’t keep me from pouring over the Arabian Horse World magazine that came to my house every month. When I was a teenager (so, a long time ago!), I read an interview of one of the old-time breeders of top notch Arabians down in California. This man, John Rogers, had acquired one of the most beautiful Arabian stallions in the world—Serafix—from a famous stable in England. Rogers knew that his farm would become even busier with Serafix on the property, so he had recently hired a man to be his new stable manager, Murrel Lacey. Rogers was giving Lacey the tour of the place and began commenting on what he wanted done.

He walked by Serafix’s stall and grumped to Lacey, “There’s that damn rooster! He sits there like he owns the place, and crows and drops feathers and craps all over that stall door. I want something done about that rooster, it’s driving me crazy!” Rogers relates that after he finished his grousing, Murrel strode over to the stall in his cowboy boots, reached out his hands, grabbed that rooster and wrung its neck. Problem solved!

Okay, that’s a bit shocking to visualize, I know—but there’s a really great lesson here for us about the Catholic approach to temptation: just kill the damn rooster! If there’s some evil temptation that is, symbolically, acting like it owns your heart, raising a ruckus in your life and making messes everywhere—just get rid of it! Stop talking and complaining and thinking about it and take action. It’s amazing how many days, weeks, months, even years go by as we fuss and dislike a recurring temptation, but we never do anything about it!

God has given you a share of His authority—you have the choice and the capacity to not let your temptations run rough shod over your life. But you can’t be a bystander and a complainer about your own life—you need to act.

Renounce evil. Resist temptation. The Bible reminds us that sin speaks to our hearts, but we can resist it—stand up to the devil, and he will flee from you. Have the heart of a warrior—and know that when you resist temptation and reject the devil, you have some powerful allies in this battle: St. Michael the Archangel, the heavenly hosts, all the saints in heaven, and the Almighty Lord Himself! Call upon them! When temptations assail you, when they try to beguile you and weaken you—when they crow and crap and try to take over, stride forward, grab that rooster, and … well, you know what!

Now, this doesn’t mean that temptations will immediately disappear when you wade in and resist them. Anyone struggling with a difficult compulsion or addiction knows this isn’t true. But, really, we are all sin addicts, aren’t we? Just let us get a little sleep-deprived, or low in blood sugar, or frazzled, and suddenly we are giving in to temptations to insult, gossip, lie, steal, hurt and worse! Behaviors we thought we vanquished back in middle school can reappear with shocking and distressing frequency! It seems that once we get rid of one rooster, another jumps on that stall door and starts the crowing and messing all over again!

Don’t get discouraged! Our Catholic vision of spiritual battle teaches us that we are not promised success according to our timeline, but we are called to engage! To struggle and try, to call upon reserves we might not even believe we have and refuse to be mastered by anyone or anything but our One True Master—our Loving Father in heaven.

“The greatest danger for a Christian is to underestimate the importance of fighting skirmishes. The refusal to fight the little battles can, little by little, leave him soft, weak and indifferent, insensitive to the accents of God’s voice.”

St. Josemaria Escriva, Christ is Passing By, 77

So, with the story about the rooster, I’ve explained how the Catholic Church encourages us to wade into the battle with hesitation, confident in our authority and our ability, in the name of Jesus Christ, to face and renounce the temptations that come our way. I’ve also encouraged you to persist in the struggle—that just because we choose to resist temptation doesn’t mean that God is going to quickly remove it from our lives. The victory comes through the struggle, in enduring. Victory comes when we surrender to God alone, not to our own expectations of success and especially when we refuse to surrender to temptations. This is how we deal with the temptations that assail us from outside ourselves—from other people, from the Evil One. What about those that originate inside ourselves—from our own weaknesses, thoughts and emotions running wild?

So to address that aspect of temptation, we need to explore another lesson rooted deep in our Catholic culture: the hard work of self-discipline and self-mastery that is the life’s task of every Christian. Once again, I’m going to use an analogy that has to do with horses.

Another thing I love to learn about is the process of training called “natural horsemanship”—it’s a process of learning to speak the language a horse understands, and then asserting yourself as the leader of your horse’s “herd”—in a way that is gentle, perfectly understandable to the horse, and focused on becoming a team. I love watching the amazing process of a trainer entering an arena with a “literally” wild horse and, in the course of a couple of hours, having that horse calm and trusting and willing to submit to being ridden.

In addition to just being cool and exciting with regard to horses, there’s a critical spiritual message here for us about the spiritual struggles we face against temptation: be patient and work with yourself, not fight against yourself. In this analogy, your will or your soul—the part of you that decides and chooses and judges—is the rider. Your emotions, thoughts, impulses and body are like the horse. This is a classic Catholic understanding of the human person—we are created as a hierarchy of components or dimensions—will controlling thoughts and emotions, making decisions about how to respond to impulses and the body’s needs in ways that serve the whole self. Ruling, with gentle and firm dominion, over the “lower” parts of our human nature—so that we can harness that energy, vibrancy, and power on our pilgrimage through life.

Our fallen human nature wants to turn us upside down, so that our bodies’ needs and our emotions rule what we think about, and then our thoughts running wild dictate our judgment about what is right and wrong. This is analogous to the horse grabbing the bit and running away from the rider. It’s a sure way to get nowhere, to be frustrated, and it’s dangerous. The same is true for you—the job of a Christian is to cooperate with God’s design for our humanity. That’s how we journey to heaven—as embodied souls, whole and integrated, with our souls in command and choosing. If your goal is to get to heaven, then you’ve got to take control of the wild horse you’ve been given and work together!

We Catholics do not believe our bodies, emotions, and thoughts are depraved—we are fallen, sinful beings, yes, but still we are made in God’s image and likeness. Each person is a magnificent, unrepeatable, precious creation of God. So, getting control of this wild horse we ride through life should not be the equivalent of bronco-busting! We do not want to break the spirit of this horse. We don’t hate it or reject it or want to beat it down and force submission. This is a recipe for failure, for weakness, for deep sorrow and frustration.

So, the way to resist temptations, then, is not to beat down the self, but to redirect our energies—we need to patiently work with our selves in the same way a good rider can take a fractious, undisciplined colt and turn him into a winner! It’s amazing to watch a good rider begin to teach a young horse how to work together—infinitely patient, asking often, ignoring foolishness and failure, rewarding every instance of cooperation and submission.

What if we treated ourselves this way? What if, instead of doing the equivalent of getting out the riding crop, the painful bit and spurs, the raging anger, we just took a deep breath, recognized the challenge, and tried again? How often, when fighting temptations to sin, we also end up rejecting the God-given gifts of emotions, desires, thoughts and energy. These parts of us have been twisted and misused, yes, and must be corrected and disciplined—but not destroyed!

A good rider understands that a young horse can’t fully comply with his requests—he doesn’t have the ability to concentrate, the presence of mind to submit while retaining impulsion and energy, and he isn’t physically capable either. A good rider is patient, breaks complicated movements into smaller, do-able pieces, and gives his horse confidence to be unsure, to try, without fearing punishment. A great rider looks for long term success, not short term gains that sacrifice true training. Again, what if we treated ourselves this way?

Do you struggle with a temptation that has been controlling you for a long time? Don’t feel up to the challenge? Be patient! Focus on the performance you desire, not the bad behavior you’re getting! Break down the virtue you need into small steps—take them, ask yourself often, ignore bobbles and missteps, and reward effort.

“Don’t let discouragement enter into your apostolate. You haven’t failed, just as Christ didn’t fail on the cross. Take courage! … Keep going against the tide.”

St. Josemaria Escriva, The Way of the Cross, 13th Station

Know that, over time, your will can gain greater control of your body, emotions and thoughts—and then your energies, power and vitality can be harnessed to progress even further in virtue. Life becomes a joy and a great adventure—the way forward to the life Jesus desires for us: “I came that you might have life, and have it to the full.”

Perhaps the worst temptation we can give in to is to feel hopeless, discouraged and alone—that’s the very atmosphere of hell. Our Catholic vision of the human person is that we are designed for greatness, for excellence, by the grace of God and by the support of the communion of saints that surround and inspire us. Never give up on yourself, never consider yourself too far gone, too sinful. Grace is always available to us. God’s mercy is unlimited, unless we refuse to seek it. God’s deepest desire is for you to be whole, vibrant, fully alive and united forever with Him. This is the reason to fight temptation—so that we can embrace the truth about ourselves and our destiny!

Let’s review our two images from my “horse stories.” First, when temptations assail you, don’t let them enter your heart and mind and make a home there—remember that rooster! Second, to discipline yourself to pursue virtue and avoid temptations, remember the image of the horse trainer. Work to exercise the kind of righteous and Godly dominion over yourself that leads to a partnership, a marvelous dance, a union of will, mind, emotions and body that allow you to race toward your goal—with all the beauty and complexity and vitality that God designed a human person to possess.

Our Catholic vision of fighting temptations is not so much about focusing on the temptation at all, really—it’s about focusing on virtue, on Godliness—and in this way, we take out the power of the Evil One from the start. If every time we are tempted by what is unholy and sinful, we turn to the Lord, repent and seek His help, God will be served and we will come out victorious in the end. Do not be afraid! If you endure, victory is assured!

So where is it that we get help to deal with temptations in these ways? From prayer, the Bible, good counsel, but especially in the confessional—the Sacrament of Penance! Whenever you fall into sin, turn to the Lord’s mercy, confess your sins and receive absolution—your sins are removed, destroyed, wiped away! The grace poured out into your soul through a good confession will sustain you, heal you and inspire you. God is, after all, so much greater than the evil that seems to surround us—both the evil coming from outside and the evil inside us.